Listen to “ish” on Soundcloud.

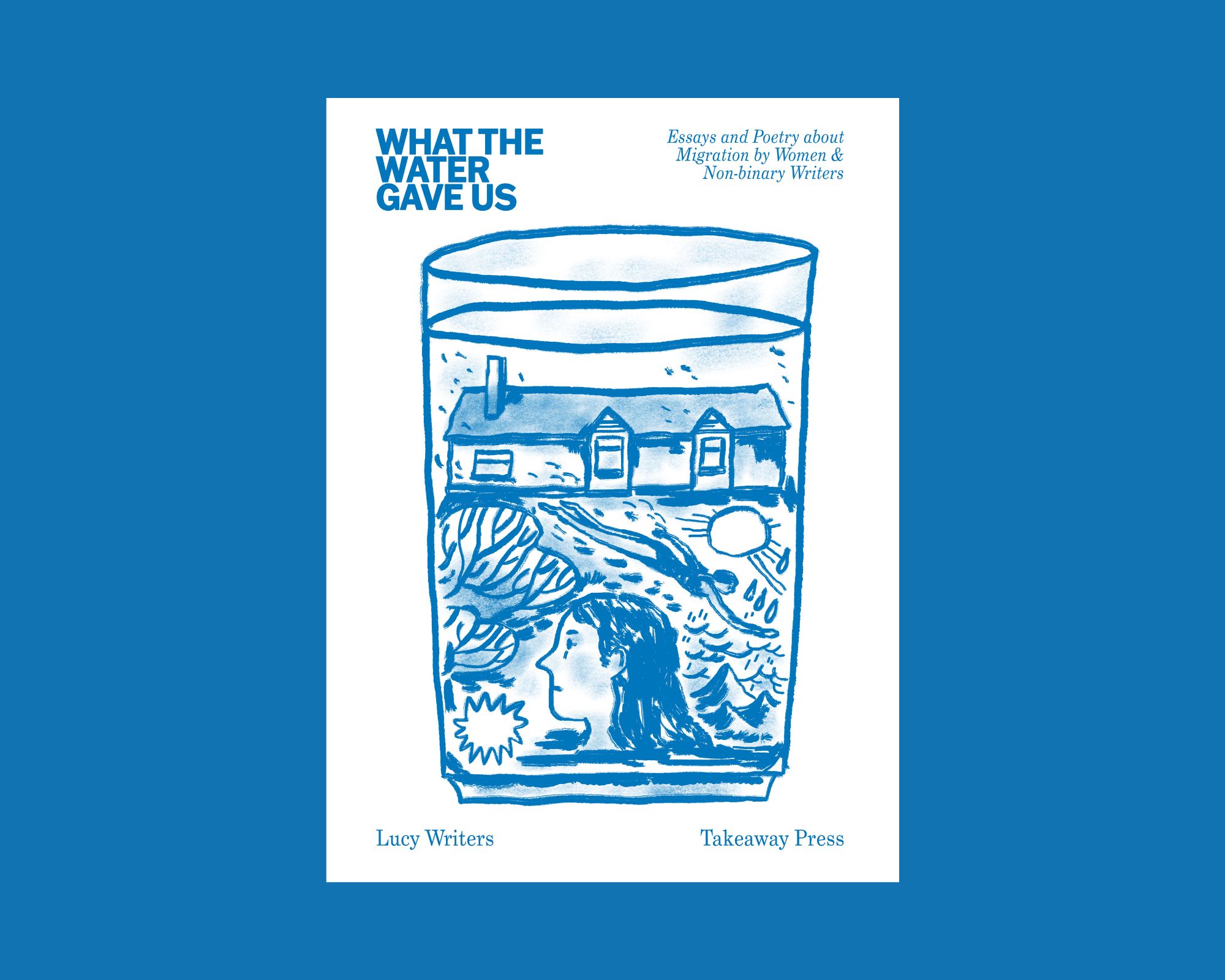

This piece was written in 2022 and published in summer 2023 in What the Water Gave Us, an anthology by women and non-binary writers from migrant backgrounds, published by Lucy Writers and Takeaway Press. The first print run has sold out and I’m grateful to editors Elodie Barnes and Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou for permission to reprint here. A reprint will be announced at the link above, and will be available to purchase in The Mosaic Rooms, Tenderbooks, The South London Gallery, Camden Arts Centre, Brick Lane Bookshop, Burley Fisher Books and many others.

ish

from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free

Was I the only Jewish child who prayed for the Messiah not to come?

*

Being a British Jew is and was an education. Steeped in education, of all kinds; in obedience, walking the line. Rendering unto Caesar while keeping yourself to yourself. I didn’t want to stay in this country because it felt good, but because, in the language of 80s graffiti, I woz ere.

What I really learned in that education, the dog whistle that came unerringly from both the secular state and my conservative religious community, was that I didn’t and could never belong: here, or anywhere, in the present as it is. Sure, there might be a future – if only I prayed hard enough for Mashiach – in which I could exist, as there had been a past that had been brutally and repeatedly severed.

But the present, here-now? No. That was for the goyim. We were just treading water, holding our breath.

*

I think of Susie (Christina Ricci) – birth name Feygele, anglicised on her arrival at Southampton fleeing a pogrom in Ukraine – going under as her ocean liner is bombed days out from New York as she once again flees, this time the Nazis, in Sally Potter’s film The Man Who Cried (2000). I think of the water that surrounds her, and the flames burning impossibly on it. Of how moments before, her friend Lola (Cate Blanchett) was swimming Esther Williams-graceful laps in the ship’s pool. Water that we swallow can swallow us up.

*

Mi’ma’amakim: from the depths. This is where David says he cries from in Psalm 130, translated into Latin as de profundis. The loss is real, the grief, the lostness. But I have come to feel that the response is all wrong. No-one owns or is owed land, dry or otherwise.

Dried. European Jewish settlers in Palestine planted invasive eucalyptus to ‘dry out’ what they characterised as swampland. As Amjad Iraqi writes for +972 Magazine, the dispossession continues. In a 2015 article, he quotes Ali, a Naqab Bedouin citizen of Israel whose village, Atir, is being erased by settler afforestation. ‘They tell us that a plant brought over from Europe has more rights than a non-Jew who was born and raised here’.[1]

Intensive plantation and farming in the desert by Israeli settler-occupiers has dried out the Jordan river to make Jordan one of the most water-scarce nations on the planet. The Jordan – Yarden in Hebrew – is the river that defines the border of Zionist Israel, a long-imagined line that is woven into the songs and stories I learned at Hebrew school, the river that stands opposed to the ‘rivers of Babylon’ that Boney M sang about on my parents’ record player, covering the Melodians’ Rastafari version of Psalm 137. Despite its demonisation as an anti-Semitic phrase, ‘from the river to the sea’ was a Zionist slogan originally, as Seraj Assi writes for Ha’aretz, describing European Jews’ territorial ambitions in Palestine.[2]

Palestinian-American scholar Maha Nassar writes back to those calling the phrase anti-Semitic by exploring the liberationist anti-colonial context of the 1960s in which the phrase was taken up, and continues to be used, by Palestinians.[3] Three years on from Nassar’s piece, which responded to the unjust firing of African-American author and activist Marc Lamont Hill for his use of the phrase, Nadim Zahawi made the use of the slogan by student activists a referrable offence on UK university campuses.[4]

*

Immersed in not-belonging, in not being present, the other thing that I learned (that I was not supposed to learn) to see was policing. Judaism is, famously (and deservedly famously), a religion of purity codes: what you can and can’t eat, who you can and can’t marry, what you can and can’t do to your body, who is and is not Jewish. No in-betweens allowed.

There is no -ish in Jewish. No fluidity, at least in the conservative community in which I was raised. That meant equally that others could not enter, and that I could not escape. Just when you thought it was safe to get back in the water.

Frida Kahlo’s father, Carl Wilhelm/Guillermo, was not – as she claimed – a Hungarian Jew from Arad, according to German historians Gaby Franger and Rainer Huhle Schirmer’s 2006 book Fridas Vater. Art historian Gannit Ankori observes that Kahlo would not be strictly considered Jewish anyway, as Judaism is matrilineal, but Ankori draws attention to Kahlo’s invocation of her father’s claimed Jewishness in the face of anti-Semitism, including to shut down Henry Ford.[5] Distancing herself from her father’s Germanic lineage during the war years allowed Kahlo to take a stand, and simultaneously, to make a strike against or escape from her mother’s intense Catholicism.

It was also a way for her to keep company with Diego Rivera, the descendant of conversos, the Jews of Sepharad/al-Andalus, the Muslim Iberian Peninsula, who were forcibly converted by the Reconquista; although recent research suggests that Rivera was also staking an unproven claim. In Kahlo’s and Rivera’s claims, which also become claims to each other in a famously tempestuous and definitional relationship that also made a complex Modernism, Kahlo and Rivera make visible the often-ignored extent of Jewish diaspora, its complexity, and its role in empire.

María Rosa Menocal notes in her exquisite book Shards of Love: Exile and the Origin of the Lyric that Cristóbal Colón took along a Sephardi Jew to act as interpreter, as he planned to land in India and knew that there, Arabic would be the lingua franca. Menocal theorises that Colón himself might have been a converso, possibly a crypto-Jew or Marrano (meaning: a dirty pig, although spanishdict.com notes graciously that in modern Spanish it is no longer used of Jews), one who practiced Judaism in secret. Menocal lingers on the fact that the Santa Maria sailed the very same day that the Jews expelled by his patrons Ferdinand and Isabella sailed from Cadiz.

Imagine the encounter in what Colón misnamed Hispaniola, little Spain, of an Arabic-speaking Jew in exile and a Taíno translator and diplomat. What warnings could the former have given; have failed, believing he was securing his own dry land, to give.

*

I hear this as a story of traverso as much as converso. It asks: how can we move ethically in diaspora, not lose ourselves in the depths? It reminds me that I bear necessary witness to the entanglement of here and there, however hard I wished the Messiah away. I can’t simplify or get stuck. I bear responsibility. It goes deep. The depths are not abstract, but geographical; military targets. Not just here-now, but then.

In 2012, I re-read the Song of Songs in Ariel and Chana Bloch’s translation, a poem that had been presented to me as erotic, as feminist. As if. In their introduction the Blochs note, ‘Jerusalem is the centre of [the lovers’] world… but the geography of their imagination reaches from the mountains of Lebanon to the oasis of Ein Gedi, from Heshbon in the east to Mount Carmel on the sea’.

I am dependent on the Blochs’ translation and notes because I can’t read the Hebrew fluently, despite daily lessons at primary school that I have repressed. But I start to track the references to oases and watersheds, such as the mountains of northern Lebanon, where ‘living waters’ run, which ‘feature prominently in the geography of the imagination of ancient Israel’, as the Blochs note.

Why? Because water is power. Water wars traverse millennia in Palestine. The Song of Songs is a militant hymn, a battle map, its vision of Edenic plenitude dependent on conquest and colonisation. In song 3, threescore warriors attend Solomon’s bed. There is nothing romantic here.

I write a version of song 4:12-15 that goes:

the cinnamon peeler’s wife

is out on strike : saffron pickers

raise their stainèd fists : the rose, its

dethorner, its packer protest :

lo, even spikenard takes a stand, refuses

access to everest. Solidarity, o! lovers

of words – of bodies – of spices. Ein Gedi,

two miles from the 1949 Armistice Agreement Line,

is not everyone’s oasis.

Translation can be a way to be in ethical relation, because it is always ish. My version is no more or less accurate or pure than any other rendering.

To be traverso is – another thing I learned that I was not supposed to – to reject purity and purism, those forms of policing. To be in the in-between, and listen to it.

*

There seems to be a queasy resonance for many critics between Kahlo’s suffering and her Jewishness, or claim to Jewishness.

I like more the argument that it was part of what connected her to Leon Trotsky, one of her many lovers, an internationale of those who stood outside the status quo. Philosemitism is deeply problematic, and I do not treat her claim – if it was an evasion of her Germanness – lightly. But, out of love for her work, I want to stake a claim to her claim as, at least in part, an internationalist act of solidarity at a time when Jews fleeing Nazi Europe were being turned away from safe harbour in the Americas.

The thing that I am still learning from being a diaspora Jew is internationalist solidarity. That it cannot apply to some, and not others. That it cannot be about creating a scale of suffering, a victimhood pyramid scheme. As Judith Butler writes, Emmanuel Levinas’s philosophy of faciality is not adequate, or acceptable, if it excludes Palestinians. Their call in Parting Ways for a Jewishness defined by a rejection of Zionism, and beyond that a Jewishness that holds Zionism to account, calls to me.

*

There is a specific act of casting-out, and specifically casting upon the waters, called tashlich. It takes place on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year (literally: head of the year) and first of the sequence of High Holy Days. In preparation for Yom Kippur, the day of Atonement, you fill your pockets with crumbs and take them to a river or stream – it must be moving water, the kind you cannot step in twice. You throw your crumbs on the water, and your sins go with them. Brush off your hands and walk away.

How easy ritual is. How little it cares for what or who is downstream.

Look again. Tashlich walks us to the water, and asks us to attend to it. Tend to it. The river has to be there, year in year out, for us to cast our crumbs. Waters are a commons, and they are all connected.

The rivers of Babylon moved the psalmist in exile because they reminded them of the rivers of home, a memory act that persisted into the song’s significance within Rastafarianism. The right of return, of reparation, cannot apply only to one nation and not others. Cannot recognise certain historic wrongs, and not others. That is a strange land, a Zion in which I cannot live.

*

Writing this piece has been a reminder that I am Engl-ish and Jew-ish. That in neither community am I fully accepted, and in neither community do I wish to be fully acceptable, and yet I bear witness and accountability for both. My own internal diaspora, my unsettled place in the in-between, does not mean I am exempt.

I do not dwell on Theresa May’s invocation of the pro-European ‘rootless cosmopolitan’, and other anti-Semitic dog whistling of the Tories around Brexit, immigration and policing. But I dwell within the borders they enforce. I dwell within the attempts to divide and rule, to sow dissensus that turns Jews against each other, and against solidarity with refugees; with Muslim communities with whom we are placed in competition and conflict despite centuries of co-operation and shared heritage; with the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities who face genocidal policies that echo the Third Reich; with Palestinian organisers, activists and exiles fighting for liberation from the river to the sea. I dwell in reflection on how easily that dissensus has been generated, how easily we are divided.

Tashlich can act as a reminder that we have been cast out onto the waters. We know how it feels. We cannot just throw our actions away, and hope that water will carry them. The past comes into the present with us, makes the present present to us. That is what I hold in my breath.

- https://www.972mag.com/bedouin-village-of-atir-to-be-replaced-with-forest-of-yatir/ ↑

- https://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/2018-12-16/ty-article-opinion/.premium/hamas-owes-its-from-the-river-to-the-sea-slogan-to-zionists/0000017f-deef-d3ff-a7ff-ffef96ca0000 ↑

- https://forward.com/opinion/415250/from-the-river-to-the-sea-doesnt-mean-what-you-think-it-means/ ↑

- https://www.972mag.com/palestine-slogan-britain/ ↑

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/23537909 ↑